Chapter Three

Gray salt water mixed with sewerage floods the ashram grounds. Lower-level offices, computer rooms, storage spaces, press equipment and workshops, newly-printed books—all submerged. Brick walls around the ashram—tumbled into rubble by the tsunami. From the balcony outside the temple where Amma (Indian humanitarian and spiritual leader) was giving a Sunday program, Amma calls out evacuation instructions to a few monks, and then joins them in the waist-deep water. The ashram and several fishing villages sit on a narrow peninsula; 15,000 surivors must evacuate to the mainland on the other side of the backwaters.

Amma orders a rope tied around the temple railing and stretched to the boat jetty about fifty yards away. The ocean water slowly recedes. People emerge from upper stories. Scores of ashram residents guide individuals along the rope, through the mud, to the boat jetty. Men use chairs to carry the old and infirm to safety. On the opposite shore, several boatmen stir into action—yelling and carrying on, they jump into canoes and pole them across the backwaters to the ashram jetty. Canoes and two motor ferries transport the elderly and the villagers cross first.

Amma queries villagers before they board, “Is everyone in your family with you?” Some don’t know. Some grieve over family members taken by the wave—children, husbands, parents—walls collapsed, trees fell. Some have left frail grandparents behind. After getting directions to hut or home, ashram monks go in search of the old and the sick, and then guide them to the boat jetty where family members wait for them.

After I help an elderly Indian ashram resident off the first evacuation ferry, she pleads with me to stay with her. “I’m going back,” I say, as I guide her into a shuttle. When I try to board the ferry back to the ashram, the young monk in charge, riding the bow as if over a stormy sea, says, “No.” He is frowning, his forehead beading with sweat. “Amma wants everyone to go to the engineering school.”

Reluctantly I join the parade of the disheveled as they wander in the hot sun towards the refugee site, ten minutes down the village main street and off onto a dirt road. My Japanese friend Eko and I—together we go. She has lived in the United States for forty years, married to an America who died recently. We stumble over the rubble outside the humongous university construction site, passing the odor from workers’ dirt-hole outhouses near temporary grass shacks. Inside, in the courtyard, I tip-toe around the sacred space of grief surrounding villagers huddled together in groups. It is they who have lost loved ones. A monk pours water for them from a pitcher.

On the way upstairs, Eko picks up a dusty piece of corrugated cardboard—her bed for the night. I’m still convinced we will return to the ashram when everything settles down. Villagers are quiet downstairs. An in-charge Western fellow, face white, eyes hollow, calls out several times,“No one…I repeat…no one is allowed to return to the ashram for any reason. Come to the third floor now and get your passports.” After the scrambling for passports settles, Indian and Western helpers serve the lunch that was floating in pots in the ashram kitchen and transported by canoe.

Filling the dead space of what-do-we-do now, many of us, Indian and Western devotees, gather to chant devotional hymns to harmonium accompaniment for a couple of hours. A white-bearded Frenchman who doesn’t speak English, joins Eko and me. Singing wanes when at around nine the evening meal of watery rice with a dollop of curry is served. Later we find out that the ashram has prepared meals for thousands of survivors in our camps and for over 15,000 at various government camps that were not prepared for the disaster. In Amma’s relief camps in Tamil Nadu, on the Bay of Bengal, 670,500 meals were served beginning on December 27. For four months the ashram would feed over 15,000 tsunami survivors in Kerala, three meals a day.

After the meal, people swarm Western and Indian men who are hauling grass mats for us to sleep on. Some of the Western guests staying in the ashram for one night only, fight over mats. The Frenchman, Eko, and I watch. After most have gone to bed, a mat-bearing friend of mine appears and hands me four. I give one to a Swedish friend, standing slack-shouldered. The Frenchman adopts Eko’s abandoned cardboard, tears it and gives me half; he grins wide, rubbing his thin back side and pointing to mine. The classrooms are sardine-like full, and so Eko and I lay our mats on the cement floor in a balcony alcove. In one of the large bathrooms, one for women and one for men on every floor, I spot the Swedish woman brushing her teeth. I hold my forefinger up and make as if to scrub my teeth. “May I have some?” She gives a vigorous nod, dabs toothpaste onto my fingertip. Once bedded down I am grateful for the scarf end of my sari for cover against the damp chill, my purse as pillow, and corrugated padding under grass mat.

In the night I am awakened by a village woman wailing.

The 2004 Asian tsunami took the lives of over 250,000 people in India, Thailand, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and other parts. On the small peninsula on the Arabian Sea in India where Amma’s ashram stands and where Amma was raised, over 150 people died. Brick homes were flattened, walls crumbled, palm frond huts washed away, loris and auto rickshaws tumbled into palm trees, fishing boats splintered.

Consoling

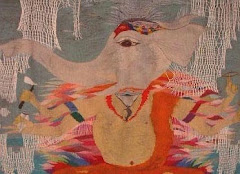

The morning after the killer wave struck, Amma consoled local refugees at the engineering school (see opening photo), held them in her arms, herself shedding tears; a few villagers lay in her lap for a long time while she stroked their backs and wiped their eyes. Throughout that next day Western and Indian ashram residents sat with villagers and comforted them. Along with scores of others, I chopped vegetables and sorted donated clothing. Several Westerners volunteered in the make-shift hospital a few blocks away; there, Eko administered Reiki and gentle massage to the injured and ill.

"We saw bodies strewn everywhere."

On the Bay of Bengal side of India, near Chennai, in Nagapattinam, twelve seaside villages washed away and more than 7,000 people died. Immediately after the wave hit, Amma sent monks from her Chennai ashram to the devastation, along with scores of local volunteers. One monk said, “We saw bodies strewn everywhere. My first instinct was to help remove them, but then I decided that the living, who were without food, needed our help more. So we started the cooking.” Volunteers prepared meals for thousands, three meals a day.

Medical team

Concurrently, Amma dispatched medical teams in twelve ambulances—staffed with nurses, paramedics, and doctors— from her high tech hospital in Cochin, to the worst-hit areas in Kerala and Tamil Nadu. Over the two days following the tsunami, they tended to 2,000 patients.

The world wanted to help

Meanwhile relief organizations all over the world were flooded with callers wanting to volunteer in Indonesia, Thailand, India, Sri Lanka—however too many well-known organizations, including governments, were unprepared for immediate action. As fast as they were able, such religious groups as the United Church of Christ, United Methodist Committee on Relief, and Scientology Volunteer Ministers, responded, without strings attached, with funding and volunteer work in various affected countries.

In many coastal towns stuck by the tsunami in Sri Lanka, people sought refuge in Buddhist and Hindu temples, mosques and churches. Local religious leaders were often the first to offer food and shelter. Survivors streamed into the temples, distraught and traumatized by the tragedy that came on an ordinary, clear blue day.

Often foreign medical aid and volunteer help from churches and private groups, began arriving as late as two weeks after the disaster. Some organizations sent out volunteers from abroad on December 26 itself. Many foreign volunteers roamed affected areas unable to locate in-place operations, or the ones they found were often ill-equipped to take on helpers. Nevertheless, thousands of local and foreign individuals who were determined to help relieve the suffering, found ways. A mass of humanity—giving their lives to meet disaster needs, with on-the-spot training, or with only instinct and common sense to guide them.

NOTE: As I prepared to post the third phase of dealing with calamity, I read this story about Hurricane Gustav relief efforts, in the NY Times today, September 1, 2008:

ABOARD A BUS FROM NEW ORLEANS — The 40-odd people boarding the black, red and white bus that the city provided late Saturday afternoon embarked on a journey of pure faith. They did not know how long they would be away or whether they would have anything to come home to. It would be many hours before they even learned where they were going….They had no way of knowing that when they finally reached their refuge, roughly 350 miles away, it would be ill-prepared for their arrival.

CREDITS:

“Bodies everywhere" quote, and some of the details about the ashram’s tsunami relief efforts, are from the photo documentary, Amma and the Tsunami: Pray & Serve (Mata Amritanandamayi Center, San Ramon, California, 2007)

Sri Lanka information is from http://www.helptsunamisurvivors.org/

Photos: courtesy of http://www.amritapuri.org/

No comments:

Post a Comment