Here in Maine, in the presence of extreme low tides, my insides feel like shore critters scattering for cover; I’m imagining the suck-out before a giant wave. The feeling doesn’t keep me away from the seaside, however. In fact I’m drawn there. I often hike down to the shore and across a low stone walkway next to seaweed and sand, over granite blocks that divide Norwood Cove and the inlet that opens into the Atlantic.

Today gulls are flapping wings after baths in mud flat tide pools, and orange star fish are feeding on mussels in crystal clear water. Off in the distance, a couple of sail boats head out to sea. On the wooden foot bridge supported by huge, square stones, I lean over the rail to view the small tidal river, every time a new sight—raging waterfall outward-bound, river rapids roaring in, streamlets gurgling in or out, nearing end of cycle.

Now, as I watch, the ebb has slowed to placid. I’ve always wanted to watch the tidal river change directions, preferring to happen upon it by chance rather than checking charts. I climb down the granite blocks, sit a hand’s reach from the water, and wait. For about fifteen minutes, water swirls in gentle circles with narrow channels continuing to ebb against flow, sounding like the rippling of a mossy creek.

The sea water slows to trembling, undulating ever so slightly, then pauses, smooth and silent like a woodland pool.

Seconds later, a ribbon of water flows inward-bound along the bridge’s granite wall, widening into streamlets, and then merging, rolling like a gentle ocean swell into the cove.

Sometimes silence at the end of cycle is the hardest part after a long journey. Many women suffer post-partum blues after giving birth, making it difficult for them to be fully present for the newborn; most men, after winning a boxing match, can only think about the next challenge; many climbers, after reaching mountaintop, take brief note of the view and plan the next trek; or the marathon runner, crosses the finish-line and while cooling down pictures the next twenty-six-mile event.

After the Greek hero Jason had sailed with his Argonauts through unimaginable dangers to recover the Golden Fleece, he was not content. He didn’t pause before continuing on with his life to experience his inner change, to view the ways his hero’s journey had made him different. Jason, by returning with Golden Fleece in hand, had won his right to rule and won the hand of the beautiful and powerful Medea, who had helped him retrieve the fleece. Yet he failed to simply be in the calm after victory, and to enjoy the presence of gracious beauty. Instead, he tired of Medea after a while and took another woman as bride. In revenge, Medea slaughtered their own young children and Jason’s new wife; and then she escaped in a chariot drawn by dragons. After that, Jason plummeted downhill in a steady decline, and when grown old and impotent, he was killed when a timber from his rotting ship fell on his head.

During the third part of the journey—the return—the traveler comes back to help others, according to Joseph Campbell in his book The Hero With a Thousand Faces. In the full cycle of the journey--departure, the initiation, return--you might say that Jason has wasted whatever he gained when he brought home the Golden Fleece.

An example of completion of all three parts of the journey can be seen in the Native American vision quest. The person, through his initiation rite during the quest, is usually given a task, something to do for his people, and ultimately for the world. The vision quest has a built-in contemplation component in the silence of the mountain-top wilderness where the person receives the vision. And the mentor guiding the vision quest waits at the bottom of the mountain and afterwards helps the initiated to understand the vision, and gives hints as to how to make it real, or concrete, or to integrate the experience into life and life’s tasks.

The Buddha, after receiving enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree, was tempted to stay in meditation, not to come back. He loved the silence too much. The wise beings pleaded with him to come out of the bliss of deep silence, to bring his new wisdom to the world.

What will we find there in the quiet of our minds? For many of us, it might be a little scary to sit in the silence after a calamity—a death of loved one, a natural disaster, job loss. Or after a great journey or accomplishment. Perhaps we might fear we'll find emptiness in the silence, that perhaps there is nothing in the quiet place inside of ourselves.

These are the times when it might be important to find a mentor, someone who has traveled the same path and who can offer guidance, like the Native American vision quest guide.

Bernadette Roberts, in her book The Experience of No Self, describes one day after she’d been contemplating in a little chapel near her home, that she no longer experienced what she knew as her “self.” Afterwards she had difficulty managing the simple task of shopping, had to keep repeating to herself, “Now I’m buying oranges, now I’m buying potatoes.” She had lived as a contemplative Carmelite nun, and so she had tools and skills, and she had faith. But she was not able to find in her religion a map to deal with her experience of no self, nor the events surrounding it. Her faith and perseverance, however, moved her along. Her experience, though it took a long time, is equivalent to the Native American vision quest, especially in her challenge towards the end in which she experienced something dreadful, beyond frightening. Bernadette writes:

I knew I was going to crack, crack wide open, but never having done this before I had no idea what would happen…I was not aware of the moment when the dreadful thing departed, for the next thing I was aware of was a profound stillness wherein there was no physical sensation at all. After a while, something must have turned my head because I found myself looking eye-level at a small, yellow wild flower…I cannot describe that moment of seeing, words could never do it justice. Let us just say it smiled—like a smile of welcome from the whole universe.

In Mac Bigelow’s Faith and Experience discussion group we talked about the Beatitudes last time, the Blessed are the meek and the rest of the Blessed ones on the list. Again I folded my arms, especially when everyone seemed to agree that God took favorites, didn’t bless everyone. One man, a minister in his eighties, uttered “Harumph!” when I suggested that we are all blessed by God and sometimes just aren’t aware of it.

And the case where no map seems to be available, sometimes we might not feel blessed, the welcome from the universe that Bernadette Roberts describes. She didn’t for a long time. She felt she’d been passed over. But she had strength of her spiritual practice she’d learned as a nun.

So I’m suggesting there are things that can be helpful in this silence of no self—which is how a profound silence can feel after a trying event. To meditate, to contemplate in nature, to write in a journal, to keep track of dreams, to find a good friend to share with who understands or at least has compassion. And to have perseverance and optimism.

Conclusion:

In Tony Hillerman’s mystery, Hunting Badger, Navajo Tribal Police Sergeant Jim Chee is sitting under a half moon with his relative, Hosteen Nakai, at the sheep-camp place. Nakai, who is dying of cancer, is Chee’s elder and mentor, the one Chee has known since childhood, the one who’s been teaching him to become a shaman. Now, on his death bed, Nakai wants to give Chee the final instructions. Chee had not been ready before now.

“I must do it now,” Nakai said. “And you must listen. The last lesson is the one that matters. Will you hear me?”

Chee took the old man’s hand.

“Know that it is hard for the people to trust outside their own family. Even harder when they are sick. They have pain. They are out of harmony. They see no beauty anywhere. All their connections are broken. That is who you are talking to. You tell them the Power that made us made all this above us and around us and we are part of the Power and if we do as we are taught we can bring ourselves back into hozho. Back into harmony. Then they will again know beauty all around them.”

These are the times when it might be important to find a mentor, someone who has traveled the same path and who can offer guidance, like the Native American vision quest guide.

Bernadette Roberts, in her book The Experience of No Self, describes one day after she’d been contemplating in a little chapel near her home, that she no longer experienced what she knew as her “self.” Afterwards she had difficulty managing the simple task of shopping, had to keep repeating to herself, “Now I’m buying oranges, now I’m buying potatoes.” She had lived as a contemplative Carmelite nun, and so she had tools and skills, and she had faith. But she was not able to find in her religion a map to deal with her experience of no self, nor the events surrounding it. Her faith and perseverance, however, moved her along. Her experience, though it took a long time, is equivalent to the Native American vision quest, especially in her challenge towards the end in which she experienced something dreadful, beyond frightening. Bernadette writes:

I knew I was going to crack, crack wide open, but never having done this before I had no idea what would happen…I was not aware of the moment when the dreadful thing departed, for the next thing I was aware of was a profound stillness wherein there was no physical sensation at all. After a while, something must have turned my head because I found myself looking eye-level at a small, yellow wild flower…I cannot describe that moment of seeing, words could never do it justice. Let us just say it smiled—like a smile of welcome from the whole universe.

In Mac Bigelow’s Faith and Experience discussion group we talked about the Beatitudes last time, the Blessed are the meek and the rest of the Blessed ones on the list. Again I folded my arms, especially when everyone seemed to agree that God took favorites, didn’t bless everyone. One man, a minister in his eighties, uttered “Harumph!” when I suggested that we are all blessed by God and sometimes just aren’t aware of it.

And the case where no map seems to be available, sometimes we might not feel blessed, the welcome from the universe that Bernadette Roberts describes. She didn’t for a long time. She felt she’d been passed over. But she had strength of her spiritual practice she’d learned as a nun.

So I’m suggesting there are things that can be helpful in this silence of no self—which is how a profound silence can feel after a trying event. To meditate, to contemplate in nature, to write in a journal, to keep track of dreams, to find a good friend to share with who understands or at least has compassion. And to have perseverance and optimism.

Conclusion:

In Tony Hillerman’s mystery, Hunting Badger, Navajo Tribal Police Sergeant Jim Chee is sitting under a half moon with his relative, Hosteen Nakai, at the sheep-camp place. Nakai, who is dying of cancer, is Chee’s elder and mentor, the one Chee has known since childhood, the one who’s been teaching him to become a shaman. Now, on his death bed, Nakai wants to give Chee the final instructions. Chee had not been ready before now.

“I must do it now,” Nakai said. “And you must listen. The last lesson is the one that matters. Will you hear me?”

Chee took the old man’s hand.

“Know that it is hard for the people to trust outside their own family. Even harder when they are sick. They have pain. They are out of harmony. They see no beauty anywhere. All their connections are broken. That is who you are talking to. You tell them the Power that made us made all this above us and around us and we are part of the Power and if we do as we are taught we can bring ourselves back into hozho. Back into harmony. Then they will again know beauty all around them.”

"...the old man had managed to hold death at bay until he saw sunlight on the mountain-top..."

Credits: Bernadette Roberts, The Experience of No Self.

Tony Hillerman, Hunting Badger.

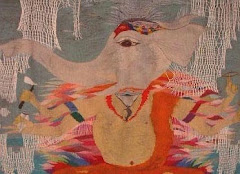

Photo and tapestry weaving by Savitri

1 comment:

Thanks, Alena. Glad you're enjoying my blog. I'll be posting more soon.

Post a Comment