Mandalas in the Sand:

Mandalas in the Sand:The Year My Brother Died

It can be scary to sit in silence after a calamity—a death of loved one, a natural disaster, job loss. Or after a far journey, or great accomplishment. Perhaps we might fear we'll find emptiness in the silence, or a loneliness too difficult to bear. In an interview with Shankar O’Callaghan, I found out how, as a young boy, he coped with the death of his younger brother, and the particular ways he found his own brand of silence.

Shankar and I had just run back from a sunset meditation on the beach with Amma, and were breathless, damp from the light rain. The lanky nineteen-year old and I ducked into the dining tent on the Gold Coast where Indian humanitarian and spiritual teacher Amma was giving a retreat as part of her Australian tour. Black clouds were closing in, wind whipping tent flaps. Other retreatants were rushing to the hall where the program would begin in a few minutes. Shankar's cupid-like face was framed with locks of sand blond hair, and he rocked back in his chair, hesitating at first. Then he leaned forward, elbows on the table, clearly eager to tell me his tale. As he started to speak, lightening struck with an ear-shattering crash of thunder, and then again. Rain pelted the roof, thudding like stones. I pulled my chair closer so I could hear him.

Shankar and I had just run back from a sunset meditation on the beach with Amma, and were breathless, damp from the light rain. The lanky nineteen-year old and I ducked into the dining tent on the Gold Coast where Indian humanitarian and spiritual teacher Amma was giving a retreat as part of her Australian tour. Black clouds were closing in, wind whipping tent flaps. Other retreatants were rushing to the hall where the program would begin in a few minutes. Shankar's cupid-like face was framed with locks of sand blond hair, and he rocked back in his chair, hesitating at first. Then he leaned forward, elbows on the table, clearly eager to tell me his tale. As he started to speak, lightening struck with an ear-shattering crash of thunder, and then again. Rain pelted the roof, thudding like stones. I pulled my chair closer so I could hear him.

“Jay was eight when he died, so he was three years younger than me. We were throwing paper airplanes in the back yard. A couple of them had gone on top of this roof that covered a back porch. He went onto the roof and . . .he’d thrown a couple of planes onto the roof. . . I was sort of yelling because I could see where they were. So I’d say, ‘Go get that one there.’ The next thing I knew the beams gave way and he’d fallen though, down about two and a half meters. He landed on his bum, legs up and head up like a ‘V’ shape. And sort of fell back onto his head then just immediately started screaming. And I ran over to him, ‘Jay, Are you okay?’ Then I ran inside and got my dad. I remember I’d told Jay off because that was the first time he’d been onto the roof, because normally I’d climb onto the roof. I’d told him off, not to step on the weak beams.

“Dad took him inside because he had a lot of pain, and dad was cuddling him and comforting him for a while. Then slowly he stopped crying, and went into a silent sort of a whimper. Then he had a couple of convulsions and went into a coma and passed out. Then we took him to the hospital. Back home I was awake all night until my step mom came and told us Jay wasn’t going to survive, and that they had him on life support until my mom could fly down from Brisbane.”

“We felt his spirit go before we turned the life support off at around eleven the next morning. It was as though at that point he felt as though . . . or we felt. . . or whatever. . . that he’d lost the attachment, and realized, ‘Okay, you’re going to die.’ That was when we felt his soul leave.

“That was a big change in my life. That was also why it was so important to have Amma’s influence. I saw how life is such a delicate thing. I don’t know how to explain it—temporal, fragile. Amma, by coming into our lives, gave us a way to deal with that. We went to India. We took my brother’s ashes to the Ganges in Hardwar and did a ceremony on the river. . . oh, I don’t know. . . we’d always wanted to go to India, Jay and me. So we finally made it to India, and. . . yeah. . . so he was in the Ganges. . . getting a dip in the Ganga. That was a nice thing. It was a special moment.

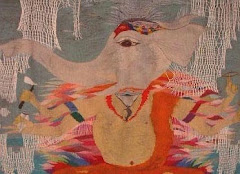

“Then we went to the ashram. Amma helped me to see it as a learning experience. I can’t think of physical examples of why it helped me. She played with me a lot. And I sat still with her for hours while she gave darshan, while other kids were running around. I became more patient. Before my brother died I didn’t used to have any patience. There was a game Amma taught us—a game with rocks. You put a handful of rocks on top of your hand and try to catch the rocks in thin air. She played tag with us. She taught me how to draw pictures, like mandalas, in the sand. Other times she’d rest her head on my lap. I'd be running on little kid energy and she used to send me to go get things for her. I was a messenger. She didn’t speak to us much but she’d play. I don’t speak Malayalam and she doesn’t speak English. Amma was the comfort; she was the supportive force after my brother died.”

When Shankar stopped we listened for a while to the rain that now pattered gently on the tent roof, thunder rumbling in the far distance. Then I asked him what he was doing now. The dimples in his cheeks deepened. “Studying medicine,” he said. “I’m enjoying science. Some people say it’s contrary, but I don’t see it that way. Everything that I see has God inside, so I don’t see the beliefs to be contrary at all. Science is a way of looking at life, trying to understand life.”

What did you notice?

The dew snail;

the low-flying sparrow;

the bat, on the wind, in the dark;

big-chested geese, in the V of sleekest performance;

the soft toad, patient in the hot sand;

the sweet-hungry ants;

the uproar of mice in the empty house;

the tin music of the cricket’s body;

the blouse of the goldenrod.

What did you hear?

The thrush greeting the morning;

What did you hear?

The thrush greeting the morning;

the little bluebirds in their hot box;

the salty talk of the wren,

then the deep cup of the hour of silence.

—From “Gratitude” by Mary Oliver

—From “Gratitude” by Mary Oliver

Credits:

Boy drawing circle in the sand: http://www.inmagine.com/paa328/paa328000004-photo

Sunset photo: www.panhala.net/Archive/Index.html

No comments:

Post a Comment