Chapter Seven

Chapter SevenBack home in the U.S., I get curious. What did that wave look like in other parts of Asia? I search the internet, something I wasn’t able to do in India. In deep ocean a tsunami travels, hardly visible from above, at the speed of a jet airliner, about 400 miles per hour; as it approaches land, the swell condenses like an accordion bellows, rises up considerably, and slows to 25 or 40 miles per hour, depending on the slope of the terrain. I grew up by the sea; a 25 mile-an-hour wave is unheard of. At six feet high, a wave traveling that fast would smash through brick walls as if match sticks.

Then I open to a picture from a beach resort in Thailand, a snap shot of a thirty-foot breaker, apparently sounding like a steam engine as it roars across sand flats laid bare when the tide was sucked out. Bathing suit-clad tourists run away, except for one woman who sprints towards the wave. Her husband and four children are out there.

One lone woman confronting a colossal wave—more concerned about her family than her life. As it turns out, they all survive without injury. Over the next days, I return to that picture; I print it; I stare at it; I can’t explain my emotional response; but maybe the image epitomizes the heroic and transformational experiences of all who lived through the tsunami—or any calamity.

Here in Maine, I told my India tsunami story on a radio talk show, at a library gathering, at a grange meeting, and in my living room. Friends and strangers gathered as if around a fire, to listen. Beyond the value of story-telling, there was another element that figured in—the digging into the archetype of calamity and the inherent potential for rite of passage.

Many enjoy seeing a movie about Israelites passing through a parted Red Sea or the voyage of Jason and the Argonauts or Hansel and Gretel getting lost in the woods. A good number enjoy watching a TV reporter out in an 80-mile an hour gale, telecasting news about the hurricane about to make land-fall, showing clips of wind-whipped sea and downed trees. In the movie “The Thin Red Line,” in a calm moment after a bloody enemy encounter, a lieutenant confronts his colonel who had never been in the fray of battle. In the midst of gunfire and from a far distance, the colonel had been shouting impossible commands over a walkie-talkie. The lieutenant, who had refused to send his men into the line of fire and certain death, asks the colonel, “Have you ever had a man die in your arms, sir?”

Watching from a distance is very different than experiencing.

What causes one person to go through a rite of passage as a result of tragedy, and another come away bitter, complaining endlessly about how awful the event was? The former faces life with a feelings of hope and inspiration, a renewed sense of purpose; the later pulls away from enjoying life, raising all barriers possible to prevent further shocks.

The answer often lies in an individual’s ability to remain optimistic in the face of all obstacles.

In India, the return to their practice of evening devotional singing was just one of that culture’s solutions against falling into hopelessness after the tsunami.

What have we to draw upon in our culture? What sustains us as individuals and as community in the face of down-slide? Over and over again as hurricanes hit the Southern United States in the past years, our community and federal government leaders have failed to supply the most simple of human needs—food and shelter. In the shelters that were provided, human dignity was shockingly neglected. When evacuations were necessary, buses were either not available or the destination shelter was not prepared. In the midst of hell-hole shelters, such as the New Orleans stadium and the FEMA boxes, no one came forward to inspire or consol, nor did anyone of that ilk arise from within the amassed refugee groups.

In his book The Hero With a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell writes: “The modern hero…cannot, indeed must not, wait for his community to cast off its slough of pride, fear, rationalized avarice, and sanctified misunderstanding…It is not society that is to guide and save the creative hero, but precisely the reverse. And so every one of us shares the supreme ordeal—carries the cross of the redeemer—not in the bright moments of his tribe’s great victories, but in the silences of his personal despair.”

“In the silences of his personal despair.” Can the average human being understand how to find redemption in such silences? Perhaps. Some come to know through an enigmatic inner gift; others by trial and error; some through a mentor; some through scripture study; others through meditation. There are many ways. I know a woman who pulled out of desolation through extended trips into the wilderness.

There are rhythmic cycles. Most find their pathway into the inner self by paying attention to their nature and feelings, by being alert and aware, watching for crossroads, for subtle changes in direction. To sustain the chosen journey, some include art therapy and journal-writing; cultivating kindness; making a living doing what they love to do, without selling out; developing support of a trusted community; going back to the land; seeing a mirror of self in others.

Joseph Campbell writes: “‘Truth is one,’ we read in the Vedas; ‘the sages call it by many names’…The way to become human is to learn to recognize the lineaments of God in all the wonderful modulations of the face of man.”

God picks up the reed-flute world and blows.

Each note is a need coming through one of us,

a passion, a longing-pain.

Remember the lips

where the wind-breath originated,

and let your note be clear.

Don’t try to end it.

Be your note.

I’ll show you how it’s enough.

Go up on the roof at night

in this city of the soul.

Let everyone climb on their roofs

and sing their notes!

Sing loud!

—Rumi

Then I open to a picture from a beach resort in Thailand, a snap shot of a thirty-foot breaker, apparently sounding like a steam engine as it roars across sand flats laid bare when the tide was sucked out. Bathing suit-clad tourists run away, except for one woman who sprints towards the wave. Her husband and four children are out there.

One lone woman confronting a colossal wave—more concerned about her family than her life. As it turns out, they all survive without injury. Over the next days, I return to that picture; I print it; I stare at it; I can’t explain my emotional response; but maybe the image epitomizes the heroic and transformational experiences of all who lived through the tsunami—or any calamity.

Here in Maine, I told my India tsunami story on a radio talk show, at a library gathering, at a grange meeting, and in my living room. Friends and strangers gathered as if around a fire, to listen. Beyond the value of story-telling, there was another element that figured in—the digging into the archetype of calamity and the inherent potential for rite of passage.

Many enjoy seeing a movie about Israelites passing through a parted Red Sea or the voyage of Jason and the Argonauts or Hansel and Gretel getting lost in the woods. A good number enjoy watching a TV reporter out in an 80-mile an hour gale, telecasting news about the hurricane about to make land-fall, showing clips of wind-whipped sea and downed trees. In the movie “The Thin Red Line,” in a calm moment after a bloody enemy encounter, a lieutenant confronts his colonel who had never been in the fray of battle. In the midst of gunfire and from a far distance, the colonel had been shouting impossible commands over a walkie-talkie. The lieutenant, who had refused to send his men into the line of fire and certain death, asks the colonel, “Have you ever had a man die in your arms, sir?”

Watching from a distance is very different than experiencing.

What causes one person to go through a rite of passage as a result of tragedy, and another come away bitter, complaining endlessly about how awful the event was? The former faces life with a feelings of hope and inspiration, a renewed sense of purpose; the later pulls away from enjoying life, raising all barriers possible to prevent further shocks.

The answer often lies in an individual’s ability to remain optimistic in the face of all obstacles.

In India, the return to their practice of evening devotional singing was just one of that culture’s solutions against falling into hopelessness after the tsunami.

What have we to draw upon in our culture? What sustains us as individuals and as community in the face of down-slide? Over and over again as hurricanes hit the Southern United States in the past years, our community and federal government leaders have failed to supply the most simple of human needs—food and shelter. In the shelters that were provided, human dignity was shockingly neglected. When evacuations were necessary, buses were either not available or the destination shelter was not prepared. In the midst of hell-hole shelters, such as the New Orleans stadium and the FEMA boxes, no one came forward to inspire or consol, nor did anyone of that ilk arise from within the amassed refugee groups.

In his book The Hero With a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell writes: “The modern hero…cannot, indeed must not, wait for his community to cast off its slough of pride, fear, rationalized avarice, and sanctified misunderstanding…It is not society that is to guide and save the creative hero, but precisely the reverse. And so every one of us shares the supreme ordeal—carries the cross of the redeemer—not in the bright moments of his tribe’s great victories, but in the silences of his personal despair.”

“In the silences of his personal despair.” Can the average human being understand how to find redemption in such silences? Perhaps. Some come to know through an enigmatic inner gift; others by trial and error; some through a mentor; some through scripture study; others through meditation. There are many ways. I know a woman who pulled out of desolation through extended trips into the wilderness.

There are rhythmic cycles. Most find their pathway into the inner self by paying attention to their nature and feelings, by being alert and aware, watching for crossroads, for subtle changes in direction. To sustain the chosen journey, some include art therapy and journal-writing; cultivating kindness; making a living doing what they love to do, without selling out; developing support of a trusted community; going back to the land; seeing a mirror of self in others.

Joseph Campbell writes: “‘Truth is one,’ we read in the Vedas; ‘the sages call it by many names’…The way to become human is to learn to recognize the lineaments of God in all the wonderful modulations of the face of man.”

God picks up the reed-flute world and blows.

Each note is a need coming through one of us,

a passion, a longing-pain.

Remember the lips

where the wind-breath originated,

and let your note be clear.

Don’t try to end it.

Be your note.

I’ll show you how it’s enough.

Go up on the roof at night

in this city of the soul.

Let everyone climb on their roofs

and sing their notes!

Sing loud!

—Rumi

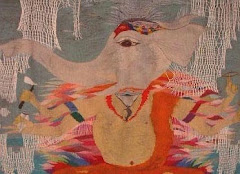

Credit: Picture at the top: from Savitri's art therapy practice

Picture at bottom: Woven tapestry by Savitri

No comments:

Post a Comment